SOS Children’s Villages Ukraine staff member tells her story of life under occupation and reaching safety

Tetiana* worked at SOS Children’s Villages in Luhansk Region, Eastern Ukraine, when the war started, and now works at SOS Children’s Villages in Kyiv Region. She recounts her life over the past two years.

I left my home and birthplace in Eastern Ukraine at the end of June 2022. I first went to Brovary, then moved and began working in Kyiv Region. My daughter and I lived under occupation for four months, and my father and brother are still living under occupation.

Creeping dusk

The war started on the morning of February 24, 2022. Our town was bombed on February 26, and by February 28, our town was entirely under occupation.

We could see heavy equipment being moved. It was dangerous, and though everyone felt great anxiety, we all believed that everything would quickly return to normal. It didn’t.

We switched to working online, which wasn’t unfamiliar because of the pandemic. SOS Children’s Villages began accepting online applications for cash voucher assistance, and we spoke with and counselled children and their families until the phone and internet connections were cut. It became difficult to work, and gradually, it became difficult to live.

The shops were mostly empty, and whatever was left could only be bought in cash. After a while, we began seeing products from the non-government-controlled area. Only one ATM was working, and the queue was endless.

The curfew was between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m. Queues in front of shops formed in minutes, with people coming from neighbouring towns and villages.

In the first days of the occupation, people protested and tried to stop the heavy equipment from moving further. With warning shots, it became too dangerous to resist.

People began leaving. Evacuation buses ran for three days, and then, due to the danger, there was nothing for a month. Private transporters took over that many people couldn’t afford. In April, these buses were shot at, and the route directly into Ukrainian-controlled territory stopped.

The evacuation route switched to a much longer one: through Russia and the Baltic countries. The cost went up to 1,000 Euros per person. I heard there were thorough checks to enter Russia, and not all could go through.

Darkness sets in

Our house is at the end of a cul-de-sac. I didn’t allow my daughter to go outside anymore. She could only visit the neighbours. She was ten then and found it hard to understand why it was dangerous.

Once, we had to go to the hospital, about two kilometres away. Along the way, she saw soldiers, tanks parked in front of supermarkets, and vehicles loaded with weapons. She understood then that the outside is no longer a safe place for children to play.

The occupiers began searching houses, looking for signs of a pro-Ukrainian movement. Many people were taken away. Some came back, and some didn’t.

Gasoline ran out quickly. Stores were looted. The occupiers broke into a nearby mobile phone shop and took only the simplest, most basic devices. From the pharmacies, they stole anti-inflammatory medications and Viagra. From the convenience stores, they stole only alcohol.

At first, the occupiers slept in tents and administrative buildings. Then, they formed their version of a local government and began breaking into and squatting in the homes of people who had fled.

The Ukrainian currency went from 1:2.5 to being equal to the Russian rouble. With this deflation, with my salary, I could buy 2 kilograms of fish, 2 kilograms of grains and 3 kilograms of sugar. A kilogram of meat of any sort was 1,200 roubles. Some meats were uneatable. We tried to get some food from people in villages who had gardens, but the demand was much higher than the supply.

Pitch black

In the first months, children attended school online. Around mid-April, teachers began preparing the schools under the occupiers’ directions. We were told, unofficially, that starting in September, the children will study according to the Russian program.

We had to leave.

On June 22, 2022, the private transporters opened a corridor towards Kharkiv. It was an expensive and risky way to get to safety, but I saw no other option. My daughter and I got on one of the buses across the occupied territory. The last stretch to the first Ukrainian checkpoint required us to walk. All that stood between us and freedom was a 4.5-kilometre walk.

Walk to freedom

It was very hot, in the high 40s. You could see the air waving over the hot asphalt. I was nervous, tense, and very emotional, but my body’s physical reaction to the heat hid my inner turmoil. My only thought was for my daughter and me to finish walking this last patch of road to freedom.

It’s strange to carry only what you managed to pack, and from now on, that will be all you have. You realize what you need and what you don’t need. My daughter and I had a bag each, focused on finishing that walk.

It wasn't easy to walk. Each step brought you closer to freedom and made you realize how far it was. Just a bit more, just a few more steps, we could see the parking lot and the buses that were going to take us to safety. Then, the shooting began.

My daughter yelled: ‘Now what?!’ I grabbed her hand and said: ‘We’re near freedom. They can’t hurt us.’ We ran towards the parking lot. People from the Red Cross hurried us into buses and immediately sent us to Kharkiv. On the overcrowded, speeding bus, my daughter fell asleep. For the first time since the war began, she felt safe.

Smell of freedom

In Kharkiv, we went through the routine check and took a train to Kyiv. Everything was different in Kyiv—the people, the air, the feeling. We didn’t have to whisper or look behind our backs. We felt better and calmer.

We’re OK materially because I work. We are in touch with the community from our hometown. My daughter even keeps attending online classes with teachers who evacuated and restarted online classes for their students. She also attends art school and dance classes.

I can see, though, that my daughter lacks independence. This is partially because we come from a smaller environment and have yet to fit into life here. And also, I tend to shelter her a lot. We’re in a safer area than our hometown, but our whole country is still under attack, and shelling can happen here, too. As long as this goes on, we will all have anxiety.

Longing for home

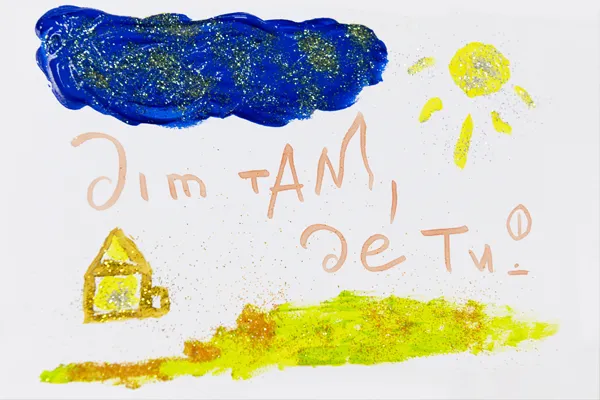

I talk with my daughter often, trying to direct her not to perceive our entire experience negatively. Yes, it is a war, but she’s a child and has to have a future. So, being always optimistic, she perceives the past two years as getting to know Ukraine.

She understands the reality, though. Back home, we could hear the shelling of the nearby towns. We were like an audience to the big theatre of war. Now, we have power cuts, worry for our family, relatives and friends, and miss our home.

Back home, life is difficult and dark. My elderly, ill father and my brother are there. They are OK for now, but they know they can easily be targeted for having someone in the family who left for Ukrainian territory.

Still, I love my roots. I hope my daughter and I can return to a safe and free home soon.

*Name changed to protect privacy.